Can Afghanistan’s never-ending internal conflict be resolved by the efforts of great and regional powers that have numerous conflicting strategic and global goals? Is it possible to stop another civil war in Afghanistan from erupting through the efforts of outside actors, between whom there is an atmosphere of complete distrust?

Experts have given different answers to these questions. Studies suggest that the Afghan conflict is a classic example of overheating and a deep sense of fatigue. Between the major international players there is no zero-sum game regarding Afghanistan’s history. The American strategy provides for a significant decrease in military presence in South Asia, Central Asia and the Middle East.

This set of factors provide for a vague opportunity to meet the interests of the major geopolitical players to try to bring Afghanistan closer to peace. However, a necessary factor in this strategy should be permanent, and multi-level pressure, on the main sponsor of radical Islamist groups in the region – Pakistan.

The widespread geopolitical practice over the last several years has shown that the system of international relations is going through a transitional phase and the contradictions of the world’s Great Powers are so significant that it is impossible to discuss any sort of parity or cooperation. The international order, for the time being, essentially has no rules or sense of traditional protocol, but has become highly politicized.

The current picture when it comes to geopolitical decorum even lacks a basic sense of decorum when it comes to diplomacy. The desire to search for compromise is, at times, a way to discuss global policy and regional decision-making processes. Meetings involving the highest echelons of power too often become mutual, public accusations.

The problem of excessive ideologization and the predominance of “-isms” in international relations is clearly visible to the naked eye. Romantic constructivist theory is not currently experiencing one of its better moments. At times, it seems that the world’s main political actors ignore their own interests and instead move from a harsh realpolitik view of the world to a much more ideological concept of how things should work.

The history of diplomacy and international relations is full of examples of Great Powers finding a compromise with far smaller and less significant players. Far less often, however, have there been cases when a global power has been able to resolve the internal conflicts of a failed state, e.g. Somalia, Afghanistan, Haiti, Lebanon, Ethiopia, Syria, Yemen, and Libya.

Failed states are, by definition, those whose very existence is under threat due to civil war political infighting and massive social upheaval that causes the country to fall into a state of anarchy without a functioning centralized government. Failed states, themselves, are of little interest to anyone. Their combined economic, military, and industrial potential is almost non-existent. According to the UN Human Development Index, failed states lag behind the poorest countries of Sub-Saharan Africa in terms of standards of living.

All of this information leads to the question: Why should any great power fight for influence in any current/past/future failed states, especially those that are not able to be controlled either from within or externally? Who needs to be responsible for problematic countries that are in a state of collapse?

The history of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union is filled with examples of great power struggles for dominance in the Third World. Debates about the necessity of past conflicts in far-flung corners of the Earth are now being re-analyzed and re-examined in connection with the ongoing Afghan peace process. In particular, observers are looking into Russia’s current diplomatic efforts, which has left the impression that there is no special geopolitical struggle for Afghanistan.

After numerous consultations, the Afghan peace process is designed to accelerate the search for lasting peace and a compromise between all of the Afghan parties involved, including the Taliban. Afghanistan has a long conflict of internal, tribal, sectarian conflict, which will most likely not come to an end. There are no signs in the foreseeable future that a resolution is possible. The enormous loss of life, instability, the fragmentation of the country, and terrorist attacks after more than 40 years of constant warfare have taken their toll on the country/

Afghanistan’s rival factions continue to play by “zero-sum” rules in every negotiating arena. In their view, everything that is good for one side is automatically bad for the other. Using this paradigm, the concept of compromise is null and void.

Government officials in Kabul and the radical Taliban movement are far more concerned with destroying or weakening each other instead of finding a logical way to govern one of the world’s poorest and least literate countries. Both sides seem to exist with permanent tunnel vision that does not allow them to understand or even care about the world’s political processes or the positions of the Great Powers.

Taliban members attend a ceremony after being released by authorities in Herat, Afghanistan. EPA-EFE//JALIL REZAYEE

Over time, the conflict becomes a heavy, boring and unpromising burden for the rest of the world. Politically and propagandistically, the Afghan story has run its course for the American establishment. Its real and potential benefits, from the point of view of Washington’s geopolitical perspective, ended long ago

There are, however, exceptions in this regard. Issues of global security and stability cannot be ignored by any major power. When the issue of international terrorism and a potential safe haven for radical Islamist terror groups come to the forefront, the powerful nations of the world are able to act together.

Memories of 9/11 are still strong for many, especially for those in the security services of many nations. The Afghan problem has always been associated with potential threats of international terrorism. After all, one cannot forget that Al-Qaeda was given a safe haven on Afghan soil by the Taliban. With the support of Pakistan’s ISI security agencies, radical Islamist groups managed to take root and gain a deep foothold in Afghanistan.

The ISI conducted and continues to carry out extremely dangerous and subversive activities in Afghanistan. They have in the past, and presumably still, finance and support the Taliban. Pakistan’s backing of the Taliban allowed the radical movement to become a key actor in Afghan politics.

At the current stage of its involvement in Afghanistan, the West is in a state of suspended animation due to the overexertion of forces. The longest war in the history of the United States is coming to a logical conclusion. The current to dealing with a country like Afghanistan is outmoded, too expensive, and does not meet the new challenges of the second decade of the 21st-century.

Soviet troops withdraw from Afghanistan in February 1989. The Soviet-Afghan War lasted for a decade and contributed significantly to the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union nearly three years later.

There is growing discontent within the US from broad segments of society as the general population do not want to see endless wars waged in far-off countries. Opinion polls show that the percentage of Americans who believe that the country should “mind its own business” has reached the same levels as were seen at the end of the Vietnam War. In their opinion, Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq are not the US’ problems.

For most Americans, what they see is an Afghan war that has been going on for nearly 20 years – since October 2001. At its peak, the military presence exceeded 120,000 troops. Today, there are less than 5,000 soldiers in Afghanistan, mostly American.

Questions about the necessity of waging endless wars were raised early on in the presidency of Barack Obama and were later echoed by his successor, Donald Trump. With Joe Biden now in the White House, the attitude to the Afghan problem has not changed course. The political establishment in Washington has, across the political spectrum of both the Democrats and Republicans, focused on rethinking domestic policy affairs.

Altruism, as defined by the late 1990s-early 2000s concept of humanitarian intervention, no longer has any capital even in a Democratic administration that would have been inclined to act exactly under those same pretences only a decade ago.

In short, Americans of all political stripes are simply tired of Afghanistan after two decades of fruitless attempts at nation-building. This is the first sign of a new American approach to international relations in light of new realities that it faces, including growing global opposition from Russia and China and stagnant political resources at home. American political scientists have repeatedly noted for the last decade that the role of the global hegemon is no longer relevant in the current system of international relations.

Even before those predictions were ever uttered in public, the much-needed geopolitical instincts of the American foreign and domestic policy establishment failed at several key moments in the post-9/11 world. As a result, important opportunities were squandered and the Trump brand of isolationism, the likes of which have not been seen in the United States since the 1930s, began to take hold more out of necessity than a need.

In February 2018, at the instigation of the United States, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani announced the beginning of a dialogue with the Taliban. The radical Islamist group, which actively uses political violence and terrorism as a method to gain power, was asked to become a “normal political party”, to participate in elections, and lay down their arms.

This defining event opened a new page in Afghan history. It changed the very essence of the conflict and created a completely new geopolitical reality. From now on, the Taliban are no longer seen as terrorists, allies of Al-Qaeda, and enemies from which the rest of the world must be protected. From that moment forward, the Taliban was designated as an integral part of Afghan society, with its own views, values, and principles.

This simple declaration is the official end of the West’s definition of statehood for Afghanistan. The main threat to international stability is the threat that an emboldened Pakistan will play in Afghan and regional affairs. Islamabad uses ISI’s connections Islamic terrorist groups to project its foreign policy positions. The potential strengthening of Pakistan’s role in the Afghan policy for global and regional security is considered by many players, including Russia and others in the region of Central Asia, as decidedly problematic. In this regard, the Afghan process should have a multi-factor and multi-vector character, which obviously eliminates potential threats.

The political atmosphere around the Afghan conflict has gradually begun to change. First, the American strategy itself has undergone major transformations that have the force of revolutionary events. Classical constructivism, coupled with neoliberalism, gave way to realpolitik. Humanitarian intervention is a thing of the past. It has been replaced by protectionism and a certain degree of isolationism.

Washington is trying, in every possible way, to switch to the “virtue of abstinence”. For the United States, where the political establishment usually has different, and often contradictory, ideas about international relations, these processes are reversible. However, it seems that in regards to American policy on Afghanistan, regardless of the administration, the policy will be to drawdown to a bare minimum.

When the Afghan War began in the weeks after 9/11, all of the regional and world powers supported the US. The UN Security Council adopted a resolution in support of the “War on Terror”. In short, at the beginning of the century, there was a global consensus – Afghanistan was a threat to international security.

Russia, and other world actors who are in rough geographic proximity to Afghanistan, wanted to end the terrorist safe havens that the Taliban allowed to be established within Afghanistan’s borders in the late 1990s. The interests of the entire international community, including its main players – the US, UK, Germany, Russia, France, India, and China – were completely aligned. Furthermore, at that time, much more attention was paid to the role that Pakistan played in destabilizing the Afghan state.

Two decades on, and those nations that are not a part of the West have become, if not opponents, then outside observers of the American policy in Afghanistan. This was not unexpected. The geopolitical and economic growth of Russia, India, and China and the failures of the Americans in Afghanistan could only end in a clash of interests. Within the United States itself, internal political and social confusion about the purpose of the whole Afghan endeavor is gradually growing. In this sort of highly contentious atmosphere, it is extremely difficult for any policymaker in Washington to think about how to completely reform the US’ strategy for Afghanistan. It might seem that the withdrawal from Afghanistan was an impulsive trick dreamt up by isolationist President Donald Trump, but as can be seen by the policies of Joe Biden in the first six months of his presidency, he has continued down the same path of ending the US’ direct presence in Afghanistan.

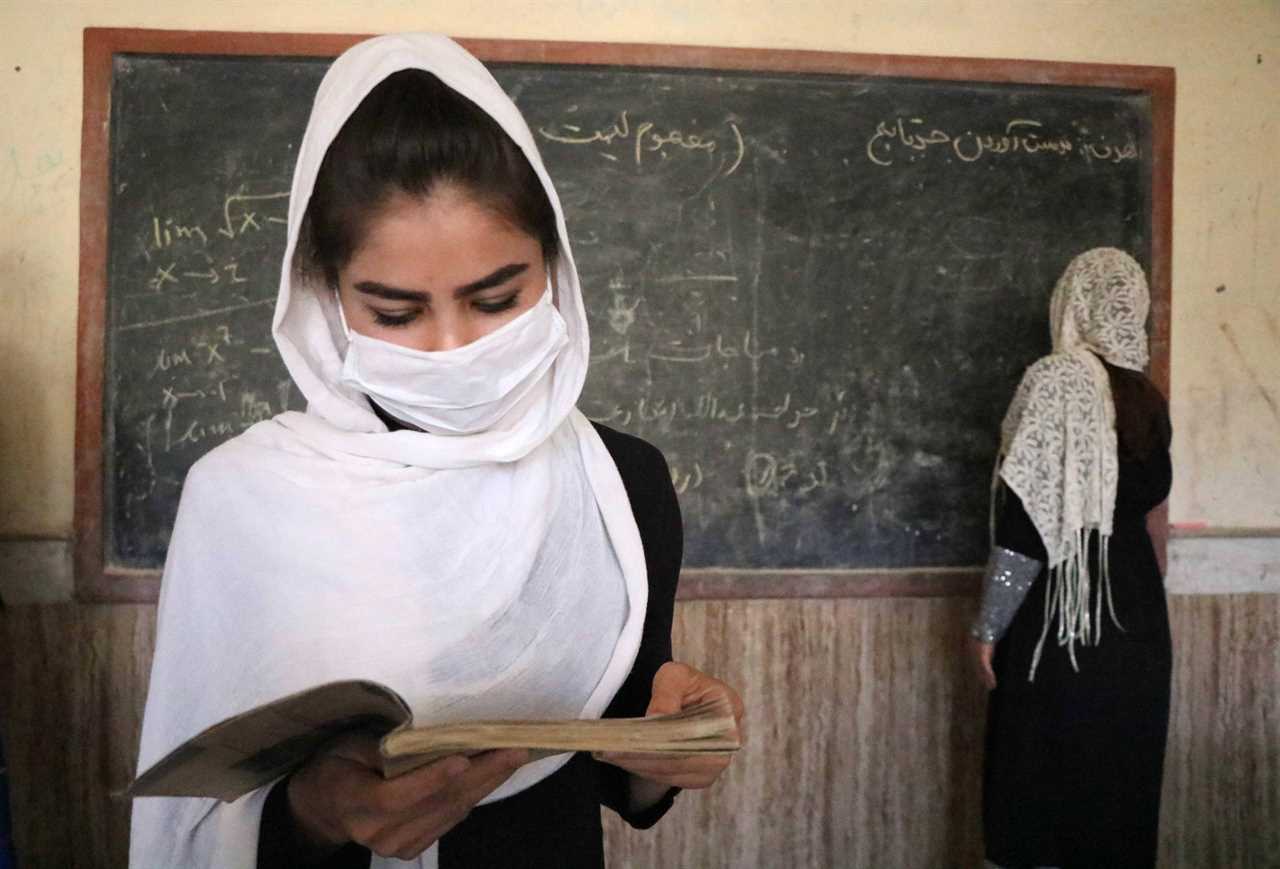

The future of Afghan society, with the radical Islamist Taliban movement now a key part of the country’s government, remains an open question. Women’s rights, which have made significant progress in the two decades since the Taliban were ousted from power, are expected to be rolled back in the coming years. EPA-EFE//JALIL REZAYEE

In short, the reality is that the US is leaving Afghanistan. And Russia, India, and the former Soviet Central Asian countries need to prepare for this while at the same time actively participating in the process around the Afghan policy. At a gathering in March in Moscow, the regional powers, putting aside (for the time being) their own disagreements, forced the government in Kabul and the Taliban to accelerate negotiations. Moscow is aware that the Afghan issue can only be resolved together. The US’ efforts alone will not be enough, and a broad regional dialogue is needed.

What was noticeable odd about the March meeting in Moscow is that India did not attend the consultations. This is most likely due to the shortcomings of Russian diplomacy, which failed to convince India, on whom much depends in the region, to attend the forum. Formally, the next meeting of the expanded “troika” – the United States, China, and Pakistan – was held in Moscow. However, given the importance and political weight of New Delhi and the strategic nature of Russian-Indian relations, the absence of Indian diplomats at the forum was a significant mistake by Moscow.

Russian diplomacy proceeds from the theoretical concepts of the school of neorealism. When it comes to Afghanistan, Moscow needs to solve several fundamentally important and strategic tasks and to ensure its national security in connection with the reduction of the American military presence and to maintain its geopolitical influence in Afghanistan.

The current stage of diplomatic efforts with regard to Afghanistan is an attempt to push the parties to a more resolute dialogue and compromise. Russia is participating in the Afghan process not to replace the United States in Afghanistan, but to compete with them for influence in this country.

Today, there is no geopolitical struggle around Afghanistan in the classical sense of the term. The old ideas of chessboards and ‘Great Games’, based on the inevitability of a struggle between external players for control of Afghanistan, is outdated and wishful thinking. That is a struggle from a bygone era; today it is no longer relevant.

Afghanistan is a classic failed state and no one wants to fight for it – not the United States or Russia; or the UK, India, and China. On the contrary, the Americans are trying in every possible way to get rid of this heavy burden, but at the moment they do not know how.

Russia’s efforts are aimed at preserving its influence on the future contours of the Afghan state without the Americans being involved. According to the agreements, the Taliban will become part of the legal political field. Members of the movement will join the government, hold ministerial posts, sit in parliament, and some will go on to head embassies.

This is a completely new reality for Afghanistan. We are witnessing a project that is truly revolutionary for this state. Its consequences are yet to be seen, and it is difficult to say how it will end. Russian diplomats are participating in the process, sometimes they are even the facilitators of certain initiatives.

As a consequence of the role, Russia retains (and exaggerates) its influence in this region. Afghanistan is a global problem and no major power can ignore this fact. The United States will continue the Afghan peace process in Turkey and Qatar. The Afghan campaign is an American story, and American strategists will continue to shape its character. The Biden administration will actively try to achieve a peace agreement between the government in Kabul and the Taliban.

UK PoliticsWorld PoliticsVideosPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions

UK PoliticsWorld PoliticsVideosPrivacy PolicyTerms And Conditions